We’re going to do another critique of the DI for this week’s class, but this time we’re going to do it with some key questions to answer, and we’re going to apply those questions to both the Monday issue and the Thursday issue. So critique both, and make sure you answer these questions when you post your comments in the Critique category of this site:

Metrics confirm that readers are most likely to appreciate stories that are somehow unexpected.

Are these four stories the ones that are most likely to somehow surprise readers? Or were they selected more because of the topics they represent?

Content selection by topic rather than development is a strategy based in advertising and marketing, not journalism, and generally does not encourage the type of habitual readership a news organization requires to be successful.

After analyzing what content was selected for Page 1, analyze how it was presented. Visual elements should not merely illustrate what something looks like; they should not say only what something is about. They should actually tell a new and surprising development of the story.

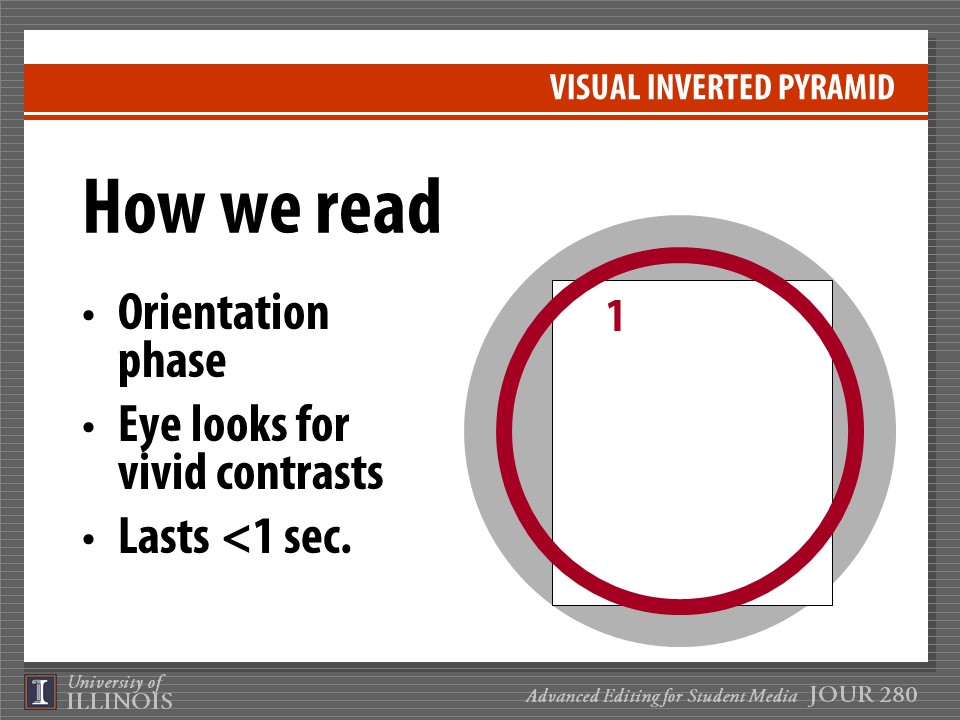

Readers are attracted by the visual vividness of an image — essentially, by how much it contrasts from the other items on the page. But this is a very fleeting attraction. The next thing they look for is information, and they seek it for the visual itself, any cutline or caption it may have, and the headline it is associated with. If those items fail to give them a reason to continue examining the package, they will go on to the next module on the page, without ever even reading the lead of the story. How effective do you think the DI’s Page 1 images were in conveying actual information?

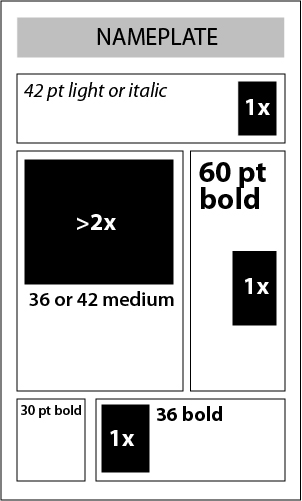

All of journalism is about making choices — one thing is more important, another is less important. We should be hierarchically ranking everything and providing a clear indication of what to look at first, then second, then third. This is done not by position on the page as much as it is by differentiation in size of the modules containing that information and the headlines and visuals that are parts of those modules. The more equal in size headlines, modules and visuals are, the less effective they become.

Think “hen and chicks.” Each page should have one hen and a flock of chicks surrounding it.

Does each front page have each of the two primary focal points it needs to have?

The first is the lead story, usually with smaller art or no art. The story should disclose something unexpected and should have the largest, boldest headline on the page, typically somewhere in the upper right quadrant but typically not stretching all the way across the top of the page.

The second is the centerpiece package. It will have the page’s dominant visual — a single picture at least twice the size of any other photo on the page. Except in very rare cases, this will not also be the lead story. At least half of the visual must be in the top portion of the page, and there can be no module on the page — including everything that goes with this visual — that is larger than the visual itself.

The centerpiece may have story text going with it but it not required to so so. It is selected not for the value of the text but rather for the value of the image itself. An old file photo can never be a dominant visual.

All other positions on the page are considered secondary. One, which may or may not exist on any given page, is called the stripper or overplay. This treatment, stretching across the top of the page but not with the largest headline, typically is reserved for stories considered “good reads” — more interesting, perhaps, than the lead story or the centerpiece but not especially urgent and without a picture sufficient to be considered as the page’s dominant visual. Pages container strippers/overplays only when the news of the day suggests they would be appropriate. Unlike the lead and centerpiece, they are not required.

After checking out the front page, look at the inside pages. Are there stories or visuals on those pages that might have been more engaging than what was on the front page?

One thing to consider is whether content slotted to fit within a specific silo really deserved more prominent play. Whenever any organization creates separate subunits like individual sections of the paper, those in charge of those sections tend to become territorial. They want their material for their pages, even if it might be as good as if not better than what is on the front page. Are their hidden gems that might increase the paper’s “talk factor” that readers might not be finding because all they see on Page 1 are the “dull but important” stories?

Sometimes, stories that don’t make Page 1 fail to do so because of correctable weaknesses with the writing or the approach taken. Are there any stories, written too routinely as a stenographic announcement without a more engaging, human-focused lead, that might have had a chance to be elevated from inside sections to Page 1?

One thing worth noting throughout the paper is the absolute lack of standalone art, which is a staple of almost every news publication. Standalone art are feature photos that don’t have story text going with them. Everything necessary is told within the cutline. Standalone photos are a great way to “brighten” a paper and include interesting, if not terribly serious, feature content. They also allow “obligatory” coverage of events and the like to be created without having to occupy a reporter’s time covering the entire event and trying to find something newsworthy within it.

What missed opportunities for standalone feature photos do you see in the Monday and Thursday DIs? Think in terms of events you know were happening, oddball things you might have seen around campus, or various projects and activities that could use a minor update that would readers could get at least some modest engagement out of.

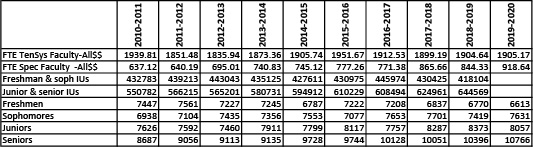

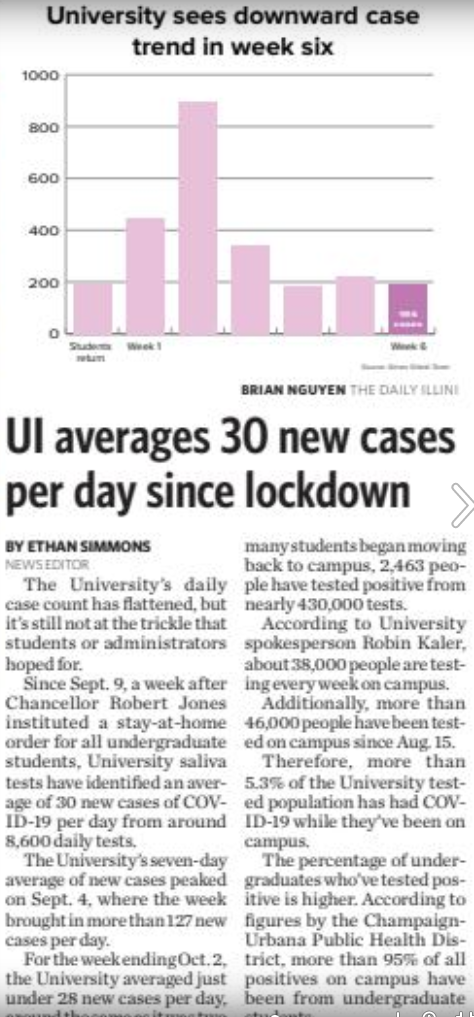

Let’s also look at infographics that appeared in the paper. Are they quickly and easily understood? Do they have a clear and significant main point? Are the statistics presented accurately and in a manner that doesn’t deceive, confuse or “spin” the topic needlessly. All graphics are important to evaluate, but I’m particularly interested in this one:

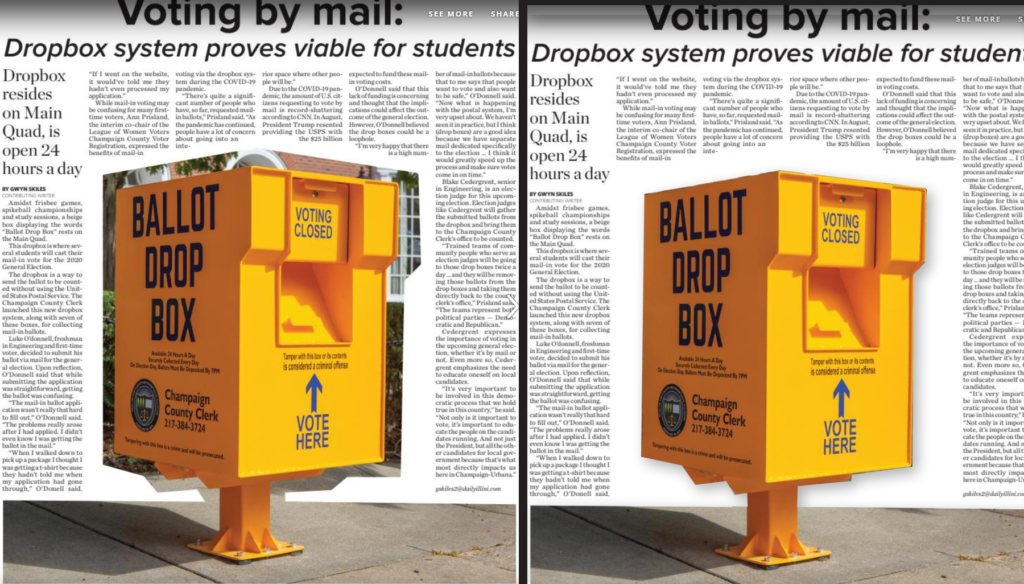

Finally, a technical point. If you’re going to do a blockout of a mugshot of a ballot box (left), why not finished the job (as done for you at right)?